肝切除术是治疗肝脏良恶性肿瘤及肝内胆管结石的常用手术手段[1]。传统的液体治疗缺乏灵敏、准确的监测指标,易导致容量超负荷或容量不足,通过影响组织灌注进而增加术后并发症发生率及病死率[2-4]。由于老年患者血管顺应性差、心储备功能弱等特点,液体不足或过量对患者围术期影响更为明显[5-6],然而迄今为止临床对于老年年龄的界限并无公认标准[7-8],摩根麻醉学老年患者麻醉管理将老年人定义为65岁及其以上人群。肝切除术中为减少肝实质离断过程中出血,目前临床仍广泛采用控制性低中心静脉压(controlled low central venous pressure,CLCVP)技术,但其对容量灵敏性、特异性差及中心静脉置管所致的并发症多等问题越来越凸显[9-11],越来越多的学者开始寻求更优的补液方案。目标导向液体治疗(goal-directed fluid therapy,GDFT)以改善组织灌注、优化组织氧供氧耗为目标,是目前最为合理的补液方式[5, 12]。本研究旨在探讨每搏量变异度(SVV)指导的GDFT对老年肝切除患者术中血流动力学、血气分析、出血量等指标的影响。现将研究相关结果报告如下。

1 资料与方法

1.1 临床资料

本研究通过湖南省人民医院伦理委员会批准,所有入选患者签署知情同意书。选取2018年2月—2018年10月于我院行择期开腹肝切除老年患者64例。入选标准:⑴ 年龄≥65岁;⑵ 择期肝切除术(两段及两段以上);⑶ 术前评估无明显严重基础病,糖尿病及高血压控制良好;⑷ ASA分级II~III级;⑸ 肝功能Child-Pugh分级A级或B级;⑹ 愿意加入该研究并签署知情同意书。排除及退出标准:⑴ 急诊手术;⑵ 术中外科评估不适宜行肝切除;⑶ 术中出现心律失常,非窦性心律>4次/min、持续5 min以上;⑷ 严重肥胖BMI>35 kg/m2。将入选患者采用电脑随机数字表随机分为两组:CLCVP组及GDFT组,每组32例。CLCVP组2例患者因术中探查不宜行肝切除而退出研究,GDFT组2例患者分别因不宜行肝切除术和过敏性休克退出研究,每组实际纳入研究均为30例。

1.2 方法

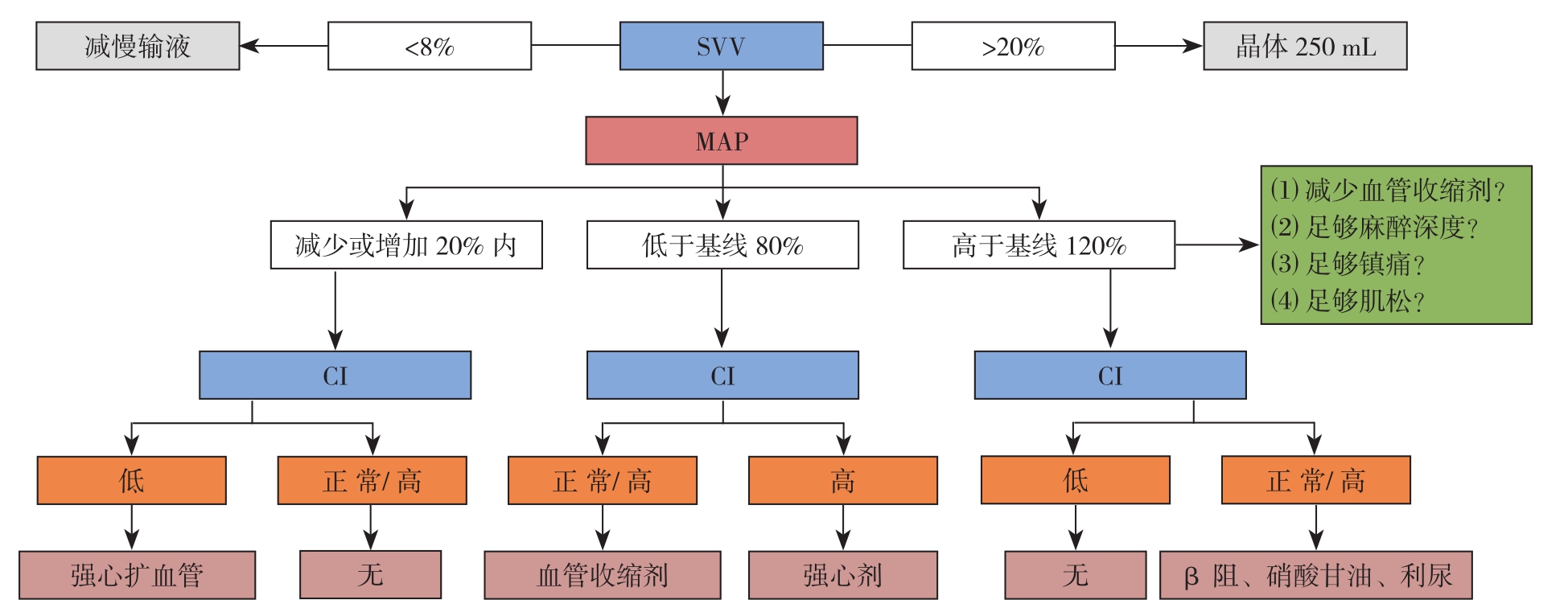

入组患者进入手术室后予以林格补充生理需要量、禁食及肠道准备造成的液体丢失。开放上肢外周静脉,常规监测心电图、袖带血压、指氧饱和度。局麻下行左桡动脉和右颈内静脉穿刺监测动脉压、中心静脉压(CVP)。两组桡动脉连接美国爱德华Flotrac/Vilige系统监测每搏量变异度,常规诱导前调定零点,调节完成后用不透明幕布遮挡CLCVP组Vilige。两组均采用常规且相同麻醉药物诱导和维持。呼吸参数:气流量2 L/min,潮气量8 mL/kg,吸呼比1:2,呼吸频率10~12次/min,呼气末CO2分压(PETCO2)35~45 mmHg(1 mmHg=0.133 kPa),采用静吸复合麻醉。维持鼻温≥36 ℃,每小时尿量>0.5 mL/kg,血红蛋白>80 g/L。CLCVP组由同一麻醉师行CLCVP补液,维持平均动脉压(MAP)65~100 mmHg,CVP 2~8 mmHg;GDFT组控制SVV在8%~20%,心脏指数(CI)>2.2L/(min·m2)(图1)。

图1 GDFT组补液方案

Figure1 Fluid supplementation scheme in GDFT group

1.3 观察指标

比较两组患者诱导前5 min(T0)、进腹时(T1)、第二次肝血流阻断时(T2)、关腹时(T3)、手术结束时(T4)各时间点的MAP、心率(HR)、CVP、CI等血流动力学指标及pH、中心静脉血氧饱和度(SCVO2)、乳酸(Lac)等血气分析指标;统计治疗过程中晶体液、胶体液及总液体量、出血量、尿量、肝血流阻断时间等数据。

1.4 统计学处理

所有数据分析均采用SPSS 23.0统计软件。正态分布的计量资料采用均数±标准差( ±s)表示,组间比较采用t检验;计数资料用频数表示,组间比较采用χ2检验,对总体不符合正态分布的数据采用非参数秩和检验。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

±s)表示,组间比较采用t检验;计数资料用频数表示,组间比较采用χ2检验,对总体不符合正态分布的数据采用非参数秩和检验。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结 果

2.1 两组患者一般资料比较

两组患者年龄、性别、体质量指数(BMI)、ASA分级、Child-Pugh分级、合并症、疾病种类、既往手术史及手术方式均无统计学差异(均P>0.05)(表1)。

表1 两组患者一般情况比较(n=30)

Table1 Comparison of the baseline data between the two groups of patients (n=30)

资料 CLCVP组 GDFT组 t/χ2 P性别[n(%)]男16(53.3) 13(43.3) 0.6010.438女14(46.7) 17(56.7)年龄(岁, ±s) 70.13±3.1669.27±2.981.0930.279 BMI(kg/m2,

±s) 70.13±3.1669.27±2.981.0930.279 BMI(kg/m2, ±s) 23.35±1.7724.25±1.73 -1.9750.053 ASA分级[n(%)]II 7(23.3) 3(10.0) 1.9200.166 III 23(76.7) 27(90.0)Child-Pugh分级[n(%)]1级 26(86.7) 28(93.3) 0.1850.6672级 4(13.3) 2(6.7)合并基础疾病[n(%)]糖尿病 4(13.3) 8(26.7) 1.6670.197高血压 9(30.0) 13(43.3) 1.1480.284冠心病 5(16.7) 3(10.0) 0.1440.704诊断[n(%)]良11(36.7) 7(23.3) 1.2700.260恶19(63.3) 23(76.7)既往腹部手术史[n(%)] 4(13.3) 6(20.0) 0.4800.488手术方式[n(%)]肝段切除 8(26.7) 10(33.3)半肝切除 16(53.3) 16(53.3) 0.6220.733肝三叶切除 6(20) 4(13.4)

±s) 23.35±1.7724.25±1.73 -1.9750.053 ASA分级[n(%)]II 7(23.3) 3(10.0) 1.9200.166 III 23(76.7) 27(90.0)Child-Pugh分级[n(%)]1级 26(86.7) 28(93.3) 0.1850.6672级 4(13.3) 2(6.7)合并基础疾病[n(%)]糖尿病 4(13.3) 8(26.7) 1.6670.197高血压 9(30.0) 13(43.3) 1.1480.284冠心病 5(16.7) 3(10.0) 0.1440.704诊断[n(%)]良11(36.7) 7(23.3) 1.2700.260恶19(63.3) 23(76.7)既往腹部手术史[n(%)] 4(13.3) 6(20.0) 0.4800.488手术方式[n(%)]肝段切除 8(26.7) 10(33.3)半肝切除 16(53.3) 16(53.3) 0.6220.733肝三叶切除 6(20) 4(13.4)

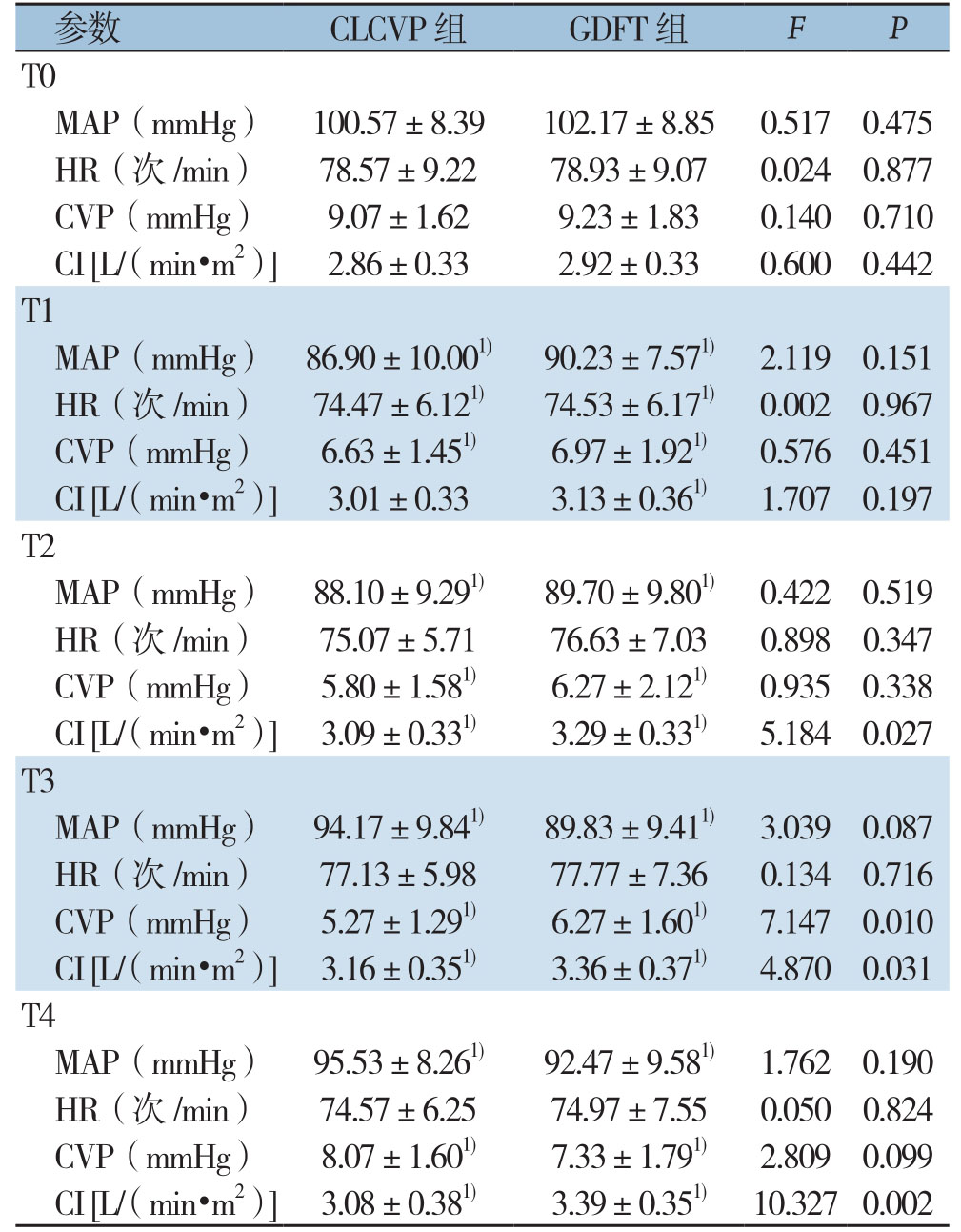

2.2 治疗过程中两组血流动力学指标比较

与各自T 0时间点比较,两组M A P、C V P在T 1、T 2、T 3、T 4时间点均明显下降(均P<0.05),H R在T 1时间点明显下降(均P<0.05),CLCVP组CI在T2、T3、T4时间点明显升高(均P<0.05),而GDFT组CI在T1、T2、T3、T4时间点均明显升高(均P<0.05)。两组间MAP、HR在各时间点差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05),但GDFT组CVP在T3时间点明显高于CLCVP组、CI在T2、T3、T4时间点均明显高于CLCVP组(均P<0.05)(表2)。

表2 两组血流动力学指标比较(n=30, ±s)

±s)

Table2 Comparison of the hemodynamic parameters between the two groups (n=30,  ±s)

±s)

注:1)与同组T0时间点比较,P<0.05

Note:1) P<0.05 vs. T0 time point of the same group

参数 CLCVP组 GDFT组 F P T0 MAP(mmHg) 100.57±8.39102.17±8.850.5170.475 HR(次 /min) 78.57±9.2278.93±9.070.0240.877 CVP(mmHg) 9.07±1.629.23±1.830.1400.710 CI [L/(min·m2)] 2.86±0.332.92±0.330.6000.442 T1 MAP(mmHg) 86.90±10.001) 90.23±7.571) 2.1190.151 HR(次 /min) 74.47±6.121) 74.53±6.171) 0.0020.967 CVP(mmHg) 6.63±1.451) 6.97±1.921) 0.5760.451 CI [L/(min·m2)] 3.01±0.333.13±0.361) 1.7070.197 T2 MAP(mmHg) 88.10±9.291) 89.70±9.801) 0.4220.519 HR(次 /min) 75.07±5.7176.63±7.030.8980.347 CVP(mmHg) 5.80±1.581) 6.27±2.121) 0.9350.338 CI [L/(min·m2)] 3.09±0.331) 3.29±0.331) 5.1840.027 T3 MAP(mmHg) 94.17±9.841) 89.83±9.411) 3.0390.087 HR(次 /min) 77.13±5.9877.77±7.360.1340.716 CVP(mmHg) 5.27±1.291) 6.27±1.601) 7.1470.010 CI [L/(min·m2)] 3.16±0.351) 3.36±0.371) 4.8700.031 T4 MAP(mmHg) 95.53±8.261) 92.47±9.581) 1.7620.190 HR(次 /min) 74.57±6.2574.97±7.550.0500.824 CVP(mmHg) 8.07±1.601) 7.33±1.791) 2.8090.099 CI [L/(min·m2)] 3.08±0.381) 3.39±0.351) 10.3270.002

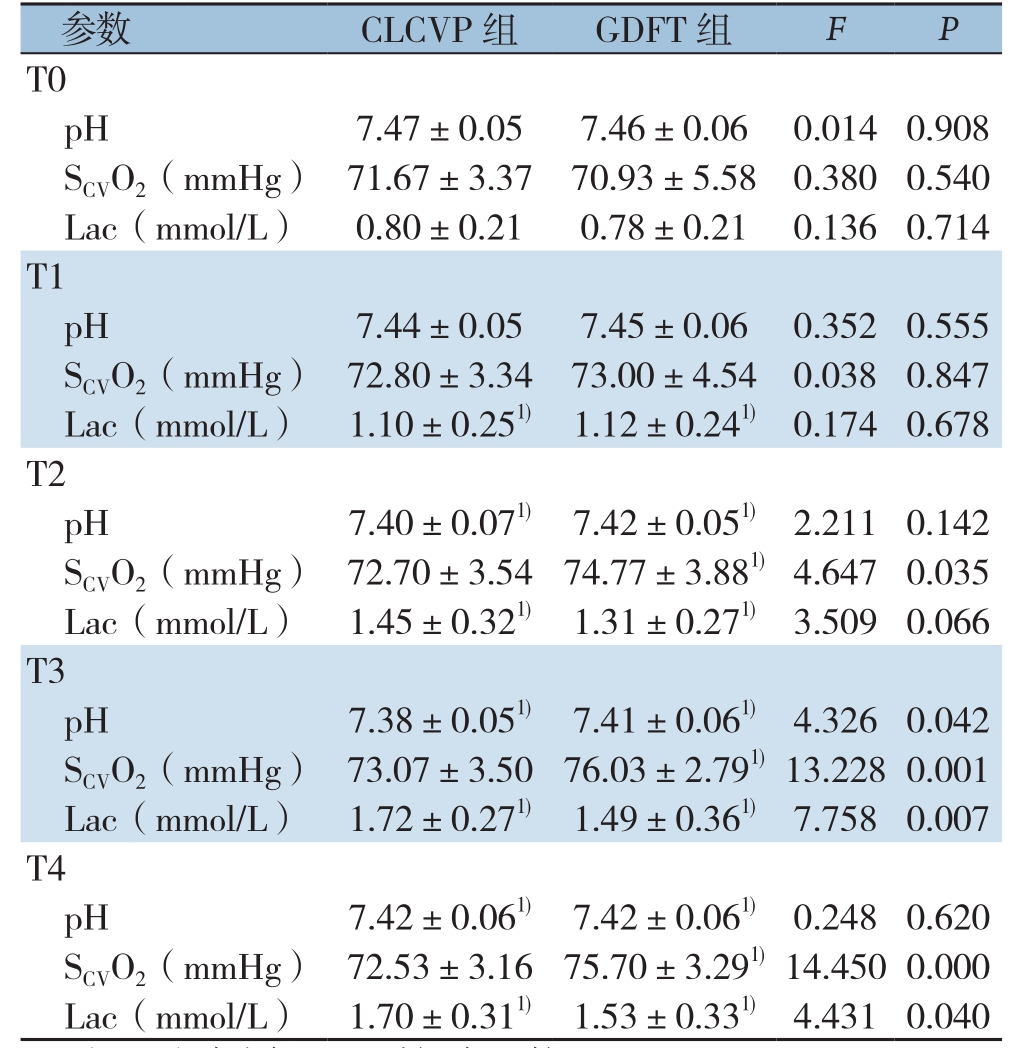

2.3 治疗过程中血气指标比较

与各自的T0时间点比较,两组血pH值在T2、T3、T4时间点均明显降低(均P<0.05),CLCVP组SCVO2在各时间点均无明显变化(均P>0.05),GDFT组SCVO2在T2、T3、T4时间点均明显升高(均P<0.05),两组Lac在T1、T2、T3、T4时间点均明显升高(均P<0.05)。两组间血pH值在各时间点均无明显差异(均P>0.05),但GDFT组SCVO2在T2、T3、T4时间点均明显高于CLCVP组、Lac在T3、T4时间点明显低于CLCVP组(均P<0.05)(表3)。

表3 两组血气指标比较(n=30, ±s)

±s)

Table3 Comparison of the blood gas indexes between the two groups (n=30,  ±s)

±s)

注:1)与同组T0时间点比较,P<0.05

Note:1) P<0.05 vs. T0 time point of the same group

参数 CLCVP组 GDFT组 F P T0 pH 7.47±0.057.46±0.060.0140.908 SCVO2(mmHg) 71.67±3.3770.93±5.580.3800.540 Lac(mmol/L) 0.80±0.210.78±0.210.1360.714 T1 pH 7.44±0.057.45±0.060.3520.555 SCVO2(mmHg) 72.80±3.3473.00±4.540.0380.847 Lac(mmol/L) 1.10±0.251)1.12±0.241)0.1740.678 T2 pH 7.40±0.071) 7.42±0.051)2.2110.142 SCVO2(mmHg) 72.70±3.5474.77±3.881)4.6470.035 Lac(mmol/L) 1.45±0.321) 1.31±0.271)3.5090.066 T3 pH 7.38±0.051) 7.41±0.061)4.3260.042 SCVO2(mmHg) 73.07±3.5076.03±2.791)13.2280.001 Lac(mmol/L) 1.72±0.271) 1.49±0.361)7.7580.007 T4 pH 7.42±0.061) 7.42±0.061)0.2480.620 SCVO2(mmHg) 72.53±3.1675.70±3.291)14.4500.000 Lac(mmol/L) 1.70±0.311)1.53±0.331)4.4310.040

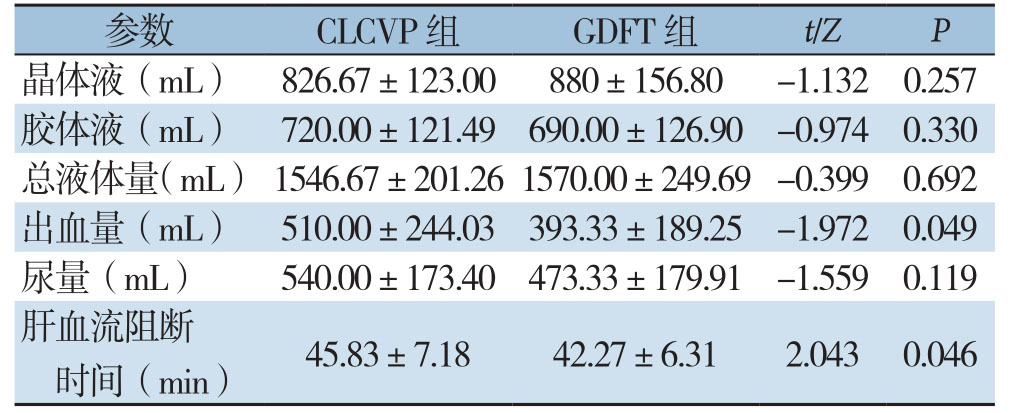

2.4 其他术中指标比较

两组胶体液、晶体液、总液体量、尿量无统计学差异(均P>0.05),但GDFT组出血量少于CLCVP组、肝血流阻断时间短于CLCVP组(均P<0.05)(表4)。

表4 两组术中其他指标比较(n=30, ±s)

±s)

Table4 Comparison of other intraoperative variables between the two groups (n=30,  ±s)

±s)

参数 CLCVP组 GDFT组 t/Z P晶体液(mL) 826.67±123.00880±156.80 -1.1320.257胶体液(mL) 720.00±121.49690.00±126.90 -0.9740.330总液体量(mL) 1546.67±201.261570.00±249.69-0.3990.692出血量(mL) 510.00±244.03393.33±189.25 -1.9720.049尿量(mL) 540.00±173.40473.33±179.91 -1.5590.119肝血流阻断时间(min) 45.83±7.1842.27±6.312.0430.046

3 讨 论

从CVP到SVV指导肝切除补液,临床工作者一直在寻找一个简单、客观、灵敏的指标来判断机体的血容量状态,行早期、个体化的补液治疗。SVV通过计算一定时间内每搏量(SV)的变异程度,根据容量负荷指标能客观准确判断血容量状态,是指导G D F T灵敏度、特异度较高的指标之一,并且在胃肠外科及泌尿外科等多领域已经证实其能减少液体相关并发症及降低住院费用[1 3-1 4]。与传统的液体治疗相比,个性化的GDFT不仅要求稳定术中血流动力学,更强调早期优化血流动力学[5, 15]。血流动力学简单常用监测指标:MAP、HR、CVP、CI,其中CI为心功能状态最重要的指标之一,能较准确反映机体器官及组织灌注情况[16-18]。通过本研究结果分析可知:两组MAP、HR总体比较无统计学差异,两组T0时间点MAP明显高于其他时间点,两组T1时间点HR较T0明显下降。同时两组CVP、CI比较有统计学差异,GDFT组CVP明显高于CLCVP组,且两组T0时间点CVP明显高于其他时间点;GDFT组CI高于CLCVP组,CLCVP组T2、T3、T4时间点CI高于T0时间点,GDFT组T1、T2、T3、T4较T0明显上升。本研究中,两组MAP、HR各时间点变化主要考虑麻醉药物诱导维持所致,同时两组MAP、HR比较无统计学差异,而CVP、SVV存在差异,可能是CVP、CI液体反应性优于MAP及HR;两组CVP、CI基础值比较无统计学差异,而GDFT组CI在T2、T3、T4较CLCVP组高,说明GDFT能指导补液使机体更趋向于最优的容量负荷状态。上述结果表明,SVV指导的GDFT能稳定老年肝切除术中血流动力学。

在肝切除术中,常采用阻断肝血流及CLCVP输液相结合以减少术中出血[19-21]。随着学者对肝脏解剖认识的不断深入,目前临床肝切除术中阻断肝血流的方式多种多样,本研究中仍采用经典的第一肝门Pringle法。CLCVP补液常对液体输注过于严格,易引起血容量不足、组织缺氧,导致血Lac升高,增加液体相关并发症。研究[22-23]表明SCVO2较混合静脉血氧饱和度可更好地判断患者组织总体灌注情况,灵敏度更高,应用方便可行。本研究结果表明:两组血pH无明显统计学差异,两组T0较T2、T3及T4时间点明显高;GDFT组SCVO2明显高于CLCVP组,GDFT组T2、T3、T4时间点SCVO2较T0上升;同时CLCVP组Lac总体高于GDFT组,T3、T4两时间点CLCVP组Lac高于GDFT组。虽然Lac、SCVO2因不能反映局部组织灌注情况而存在一定局限性,却能较好的提示机体氧供-氧耗及组织整体灌注情况[24-25]。上述结果提示GDFT能改善机体氧供-氧耗平衡,使组织灌注更佳。两组在胶晶体液、胶体液、总液体量及尿量无明显差异,但GDFT组术中出血量、肝血流阻断时间少于CLCVP组,这提示两组结果差异很可能不是液体种类、液体总量所致;可能因为采用CLCVP补液方案在肝实质离断前通常过分限制液体输注,而肝实质离断完成后过量补液扩容所致。同时提示GDFT能早期判断机体血容量状态,并及时适量调整补液。

SVV指导的GDFT能稳定老年肝切除术中血流动力学,改善血气分析,减少术中出血及肝血流阻断时间。这一个性化的补液模式正与加速康复外科理念相符[26-29],可作为肝切除补液的参考依据。老年患者血管顺应性差,心储备功能弱,本研究较普通成人肝切除研究更可能得出阳性结果。然而SVV应用需满足几个基本条件:⑴ 潮气量≥8 mL/kg;⑵ 无自主呼吸的机械通气模式;⑶ 心律整齐[5, 30],这使得其目前主要应用于手术室、ICU,不宜在各科室常规用来指导补液。本研究只选取老年开腹肝切除患者作为研究对象,并只对术中主要指标进行探讨,未涉及GDFT对老年开腹肝切除术后并发症及远期疗效及获益情况等数据分析,因此仍需多中心大样本更全面的研究试验。

[1] Yoshino O, Perini MV, Christophi C, et al. Perioperative fluid management in major hepatic resection:an integrative review[J].Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int, 2017, 16(5):458-469. doi:10.1016/S1499-3872(17)60055-9.

[2] Jammer I, Tuovila M, Ulvik A. Stroke volume variation to guide fluid therapy:is it suitable for high-risk surgical patients? A terminated randomized controlled trial[J]. Perioper Med (Lond),2015, 4:6. doi:10.1186/s13741-015-0016-x.

[3] Allen SJ. Fluid therapy and outcome:balance is best[J]. J Extra Corpor Technol, 2014, 46(1):28-32.

[4] Navarro LH, Bloomstone JA, Auler JO Jr, et al. Perioperative fluid therapy:a statement from the international Fluid Optimization Group[J]. Perioper Med (Lond), 2015, 4:3. doi:10.1186/s13741-015-0014-z.

[5] Miller TE, Raghunathan K, Gan TJ. State-of-the-art fluid management in the operating room[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol, 2014, 28(3):261-273. doi:10.1016/j.bpa.2014.07.003.

[6] Amato B, Aprea G, De Rosa D, et al. Laparoscopic hepatectomy for HCC in elderly patients:risks and feasibility[J]. Aging Clin Exp Res, 2017, 29(Suppl 1):179-183. doi:10.1007/s40520-016-0675-6.

[7] 骆鹏飞, 荚卫东, 许戈良, 等. 帕瑞昔布钠对老年肝癌肝切除患者术后认知功能的影响[J]. 中国普通外科杂志, 2014, 23(7):887-892. doi:10.7659/j.issn.1005-6947.2014.07.005.Luo PF, Jia WD, Xu GL, et al. Effects of parecoxib sodium on cognitive function of elderly patients after hepatectomy for liver cancer[J]. Chinese Journal of General Surgery, 2014, 23(7):887-892. doi:10.7659/j.issn.1005-6947.2014.07.005.

[8] 翟振武, 李龙. 老年标准和定义的再探讨[J]. 人口研究, 2014,38(6):57-63.Zhai ZW, Li L. Further Discussion on the Standard and Definition of “Elderly”[J]. Population Resarch, 2014, 38(6):57-63.

[9] 朱荣涛, 郭文治, 李捷, 等. 控制性低中心静脉压在腹腔镜肝叶切除术中的应用[J]. 中国普通外科杂志, 2018, 27(1):42-48.doi:10.3978/j.issn.1005-6947.2018.01.007.Zhu RT, Guo WZ, Li J, et al. Application of controlled low central venous pressure in laparoscopic hepatic lobectomy[J]. Chinese Journal of General Surgery, 2018, 27(1):42-48. doi:10.3978/j.issn.1005-6947.2018.01.007.

[10] Marik PE, Baram M, Vahid B. Does central venous pressure predict fluid responsiveness? A systematic review of the literature and the tale of seven mares[J]. Chest, 2008, 134(1):172-178. doi:10.1378/chest.07-2331.

[11] Fu Q, Mi WD, Zhang H. Stroke volume variation and pleth variability index to predict fluid responsiveness during resection of primary retroperitoneal tumors in Hans Chinese[J]. Biosci Trends,2012, 6(1):38-43. doi:10.5582/bst.2012.v6.1.38.

[12] Choi SS, Jun IG, Cho SS, et al. Effect of stroke volume variationdirected fluid management on blood loss during living-donor right hepatectomy:a randomised controlled study[J]. Anaesthesia, 2015,70(11):1250-1258. doi:10.1111/anae.13155.

[13] Dave C, Shen J, Chaudhuri D, et al. Dynamic Assessment of Fluid Responsiveness in Surgical ICU Patients Through Stroke Volume Variation is Associated With Decreased Length of Stay and Costs:A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis[J]. J Intensive Care Med,2018, 11:885066618805410. doi:10.1177/0885066618805410.[Epub ahead of print]

[14] Benes J, Giglio M, Brienza N, et al. The effects of goal-directed fluid therapy based on dynamic parameters on post-surgical outcome:a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials[J]. Crit Care, 2014, 18(5):584. doi:10.1186/s13054-014-0584-z.

[15] Yin K, Ding J, Wu Y, et al. Goal-directed fluid therapy based on noninvasive cardiac output monitor reduces postoperative complications in elderly patients after gastrointestinal surgery:A randomized controlled trial[J]. Pak J Med Sci, 2018, 34(6):1320-1325. doi:10.12669/pjms.346.15854.

[16] Weinberg L, Ianno D, Churilov L, et al. Restrictive intraoperative fluid optimisation algorithm improves outcomes in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy:A prospective multicentre randomized controlled trial[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(9):e0183313.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0183313.

[17] 蔡秀军, 所剑. 腹部大手术围手术期的液体治疗[J]. 中国实用外科杂志, 2010, 30(6):457-459.Cai XJ, Suo J. Fluid therapy during perioperative period of major abdominal surgery[J]. Chinese Journal of Practical Surgery, 2010,30(6):457-459.

[18] Zheng H, Guo H, Ye JR, et al. Goal-directed fluid therapy in gastrointestinal surgery in older coronary heart disease patients:randomized trial[J]. World J Surg, 2013, 37(12):2820-2829. doi:10.1007/s00268-013-2203-6.

[19] Correa-Gallego C, Tan KS, Arslan-Carlon V, et al. Goal-Directed Fluid Therapy Using Stroke Volume Variation for Resuscitation after Low Central Venous Pressure-Assisted Liver Resection:A Randomized Clinical Trial[J]. J Am Coll Surg, 2015, 221(2):591-601. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.03.050.

[20] Wax DB, Zerillo J, Tabrizian P, et al. A retrospective analysis of liver resection performed without central venous pressure monitoring[J]. Eur J Surq Oncol, 2016, 42(10):1608-1613. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2016.03.025.

[21] Ratti F, Cipriani F, Reineke R, et al. Intraoperative monitoring of stroke volume variation versus central venous pressure in laparoscopic liver surgery:a randomized prospective comparative trial[J]. HPB (Oxford), 2016, 18(2):136-144. doi:10.1016/j.hpb.2015.09.005.

[22] Ong L, Liu H. Comparing a non-invasive hemodynamic monitor with minimally invasive monitoring during major open abdominal surgery[J]. J Biomed Res, 2014, 28(4):320-325. doi:10.7555/JBR.28.20140005.

[23] Oliveira B, Prasanna M, Lemyze M, et al. A comparison between measured and calculated central venous oxygen saturation in critically ill patients[J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(11):e0206868. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0206868.

[24] Gonzalez AL, Waddell LS. Blood Gas Analyzers[J]. Top Companion Anim Med, 2016, 31(1):27-34. doi:10.1053/j.tcam.2016.05.001.

[25] Rajan S, Srikumar S, Tosh P, et al. Effect of lactate versus acetatebased intravenous fluids on acid-base balance in patients undergoing free flap reconstructive surgeries[J]. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol,2017, 33(4):514-519. doi:10.4103/joacp.JOACP_18_17.

[26] Melloul E, Hübner M, Scott M, et al. Guidelines for Perioperative Care for Liver Surgery:Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS)Society Recommendations[J]. World J Surg, 2016, 40(10):2425-2440. doi:10.1007/s00268-016-3700-1.

[27] Miller TE, Roche AM, Mythen M. Fluid management and goaldirected therapy as an adjunct to Enhanced Recovery After Surgery(ERAS)[J]. Can J Anesth, 2015, 62(2):158-168. doi:10.1007/s12630-014-0266-y.

[28] 彭浪, 王恺, 樊友文, 等. 加速康复外科理念在原发性肝癌肝切除术围手术期管理的应用价值[J]. 中国普通外科杂志, 2017,26(2):218-222. doi:10.3978/j.issn.1005-6947.2017.02.014.Peng L, Wang K, Fan YW, et al. Application value of enhanced recovery concept in perioperative management of hepatectomy for primary liver cancer[J]. Chinese Journal of General Surgery, 2017,26(2):218-222. doi:10.3978/j.issn.1005-6947.2017.02.014.

[29] 宋伟, 邹书兵. 加速康复外科在肝脏手术围手术期应用的Meta分析[J]. 中国普通外科杂志, 2016, 25(1):115-125. doi:10.3978/j.issn.1005-6947.2016.01.018.Song W, Zou SB. Application of enhanced recovery after surgery in setting of liver surgery:a Meta-analysis[J]. Chinese Journal of General Surgery, 2016, 25(1):115-125. doi:10.3978/j.issn.1005-6947.2016.01.018.

[30] Rollins KE, Lobo DN. Intraoperative Goal-directed Fluid Therapy in Elective Major Abdominal Surgery A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials[J]. Ann Surg, 2016, 263(3):465-476.doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001366.