甲状腺微小乳头状癌(papillary thyroid microcarcinoma,PTMC)预后良好,病程进展缓慢,目前临床上倾向于采用主动监测的保守治疗方法,尤其是对无侵袭和转移的PTMC患者[1-2]。低风险PTMC患者可通过颈部超声检查和常规体检进行密切监测,对随访期间显示疾病进展的患者进行手术治疗[3]。既往研究显示,与立即手术相比,主动监测能够获得更加有利的肿瘤学结局,高达15%的患者依据主动监测结果决定手术[4-5]。目前国内尚未见研究探讨立即手术和延迟手术对PTMC患者结构性复发/疾病持续等长期临床结局影响的差异。由于手术时机可能受到患者临床病理特征的影响,如年龄、性别以及颈部超声提示的PTMC直径或位置,这也是PTMC复发的已知危险因素[6]。因此,分析立即手术和延迟手术的临床结局差异时,应对患者个体危险因素进行匹配,比较临床病理特征相匹配的PTMC患者的长期临床结局。本研究以我院延迟手术的PTMC患者为研究对象,比较确诊至手术的间隔对PTMC患者动态风险分层(dynamic risk stratification,DRS)分类和无病生存率(disease-free survival,DFS)的影响,以期明确PTMC患者延迟手术的临床结局。

1 资料与方法

1.1 研究对象

以2015年1月—12月在我院接受延迟甲状腺手术的PTMC患者为研究对象。纳入标准:超声引导下甲状腺细针穿刺活检诊断为良性疾病。排除标准:初诊时外侧颈淋巴结转移或远处转移,无术前高质量超声图像,随访数据不完整,确诊时最大肿瘤直径>1 cm,最终426例PTMC患者纳入本次研究。

根据确诊至甲状腺手术(延迟期)时间的间隔,将患者分为3组。确诊时间定义为初步判断可疑甲状腺结节的时间,最终病理确诊为PTMC。从确诊后6个月内接受手术的患者被归类为短间隔组;延迟时间为6~12个月时,患者被归类为中间隔组;在初始诊断后12个月后接受延期甲状腺手术的患者被归类为长间隔组。长间隔组患者例数最少,因此每组患者根据其年龄、性别、手术范围、颈部超声显示的PTMC最大直径、甲状腺外侵犯、多灶性肿瘤和颈部中央淋巴结转移,以3:3:1的比例进行匹配。在个体风险匹配中,年龄在1岁内和原始肿瘤直径差异在0.1 cm内认为是相同的。该研究得到了我院伦理委员会批准同意。

1.2 治疗和随访

所有患者均接受常规术前颈部超声检查。手术时间和程度取决于患者要求和外科医生的决定。患有双侧多灶性PTMC或侧叶不确定性结节的PTMC患者接受甲状腺全切除治疗,而其他患者接受侧叶切除治疗。对于PTMC患者,常规进行预防性同侧或双侧颈部淋巴结中央清扫术。对有复发危险因素的患者进行全甲状腺切除术后放射性碘(RAI)消融治疗。

初始治疗后,所有患者每6~12个月定期随访,进行体格检查,并测量甲状腺功能、血清甲状腺球蛋白(Tg)、血清抗Tg抗体(TgAb)和颈部超声。对于接受甲状腺全切除术和RAI消融术的患者,在初始治疗后12~24个月利用诊断性RAI全身扫描(WBS)测量血清Tg(sTg)水平。

1.3 定义

不同初始治疗反应和结构性复发/疾病持续的DRS是本研究的主要结局指标。DRS分类采用血清Tg水平、血清TgAb水平和有/无诊断性WBS的颈部超声结果,根据患者对初始治疗的反应为4类:反应良好、反应不确定、生化不完全反应和结构不完全反应[7]。结构性复发/疾病持续是指病理学或细胞学证实的病变复发或转移性,和(或)在影像学检查发现其他远处器官出现转移性病变,Tg水平升高[8]。无病生存期(DFS)是指从初始手术到发现结构性复发/疾病持续的时间间隔。

1.4 统计学处理

采用SPSS 20.0进行统计分析,连续变量表示为平均值±标准偏差( ±s),分类变量以百分比[n(%)]形式表示。使用χ2或Fisher精确检验比较分类变量,并使用单因素方差分析(ANOVA)比较连续变量。采用Kaplan-Meier方法构建匹配数据DFS曲线。开展对数秩检验,评估组间DFS差异。Cox比例风险模型也用于评估结构性复发/疾病持续的风险因素。所有P值均为双侧,P<0.0为差异有统计学意义。

±s),分类变量以百分比[n(%)]形式表示。使用χ2或Fisher精确检验比较分类变量,并使用单因素方差分析(ANOVA)比较连续变量。采用Kaplan-Meier方法构建匹配数据DFS曲线。开展对数秩检验,评估组间DFS差异。Cox比例风险模型也用于评估结构性复发/疾病持续的风险因素。所有P值均为双侧,P<0.0为差异有统计学意义。

2 结 果

2.1 个体危险因素匹配前后的PTMC患者临床病理特征

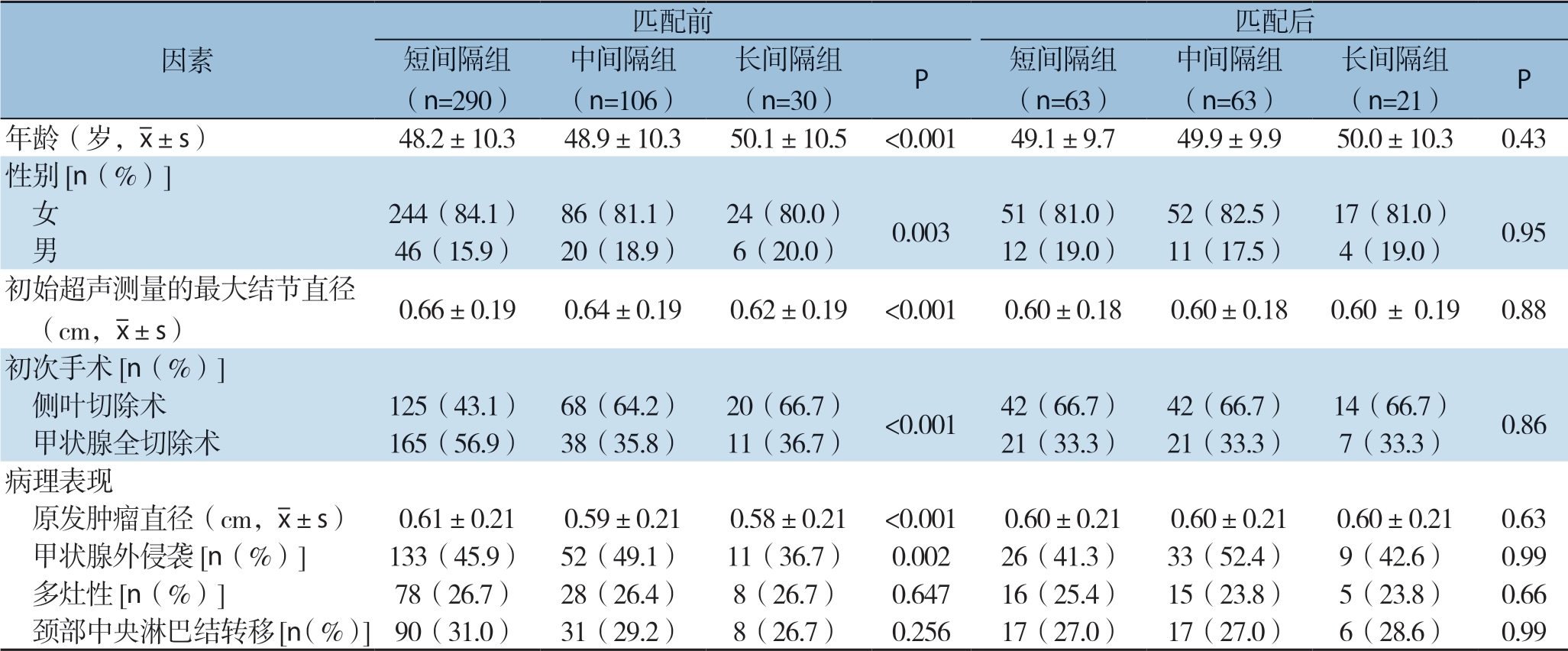

个体危险因素匹配前426例患者平均年龄为(48.9±10.1)岁;331例女性,95例男性;首次诊断时颈部超声测量的平均肿瘤直径为(0.65±0.12)cm;214例患者接受甲状腺侧叶切除术,其他患者接受甲状腺全切除术。根据手术延迟时间,短间隔组290例患者(68.1%)、中间隔组106例患者(24.9%)、长间隔组30例患者(7%)。3组患者从初诊到手术的平均时间如下:短间隔组(3.1±0.8)个月、中间隔组(8.2± 1.4)个月、长间隔组(17.4±2.2)个月。接受延期手术的患者年龄大,男性患者比例高,接受侧叶切除术比例高(均P<0.05)。此外,延期手术患者初始超声和最终病理报告显示的PTMC直径更小、甲状腺外侵袭率更低(均P<0.05)。

经过年龄、性别、超声测量的初始PTMC直径、手术范围、甲状腺外侵袭、多灶性肿瘤和最终病理证实的颈部中央LN转移等参数匹配后,126例患者分别被分配至短间隔组和中间隔组(每组63例),21例患者分配至长间隔组。经个体危险因素匹配后的147例患者平均年龄为(50.0±8.2)岁;120例女性,27例男性。超声测量的初始PTMC平均直径(0.63±0.14)cm,98例患者接受甲状腺侧叶切除术。经个体危险因素匹配后,各组PTMC患者术前和术后特征间无统计学差异(均P>0.05)(表1)。

表1 个体危险因素匹配前后的PTMC患者的临床病理特征

Table1 Clinicopathologic characteristics of PTMC patients before and after individual risk factor matching

匹配前 匹配后短间隔组(n=290)因素中间隔组(n=106)(n=30) P 短间隔组(n=63)长间隔组中间隔组(n=63)长间隔组(n=21) P年龄(岁,images/BZ_34_707_2306_732_2347.png±s) 48.2±10.3 48.9±10.3 50.1±10.5 <0.001 49.1±9.7 49.9±9.9 50.0±10.3 0.43性别[n(%)] 女 244(84.1) 86(81.1) 24(80.0) 0.003 51(81.0) 52(82.5) 17(81.0) 0.95 男 46(15.9) 20(18.9) 6(20.0) 12(19.0) 11(17.5) 4(19.0)初始超声测量的最大结节直径 (cm,images/BZ_34_707_2306_732_2347.png±s) 0.66±0.19 0.64±0.19 0.62±0.19 <0.001 0.60±0.18 0.60±0.18 0.60 ± 0.19 0.88初次手术[n(%)] 侧叶切除术 125(43.1) 68(64.2) 20(66.7) <0.001 42(66.7) 42(66.7) 14(66.7) 0.86 甲状腺全切除术 165(56.9) 38(35.8) 11(36.7) 21(33.3) 21(33.3) 7(33.3)病理表现原发肿瘤直径(cm,images/BZ_34_707_2306_732_2347.png±s) 0.61±0.21 0.59±0.21 0.58±0.21 <0.001 0.60±0.21 0.60±0.21 0.60±0.21 0.63 甲状腺外侵袭[n(%)] 133(45.9) 52(49.1) 11(36.7) 0.002 26(41.3) 33(52.4) 9(42.6) 0.99 多灶性[n(%)] 78(26.7) 28(26.4) 8(26.7) 0.647 16(25.4) 15(23.8) 5(23.8) 0.66 颈部中央淋巴结转移[n(%)]90(31.0) 31(29.2) 8(26.7) 0.256 17(27.0) 17(27.0) 6(28.6) 0.99

2.2 不同甲状腺手术延迟期患者的临床结果比较

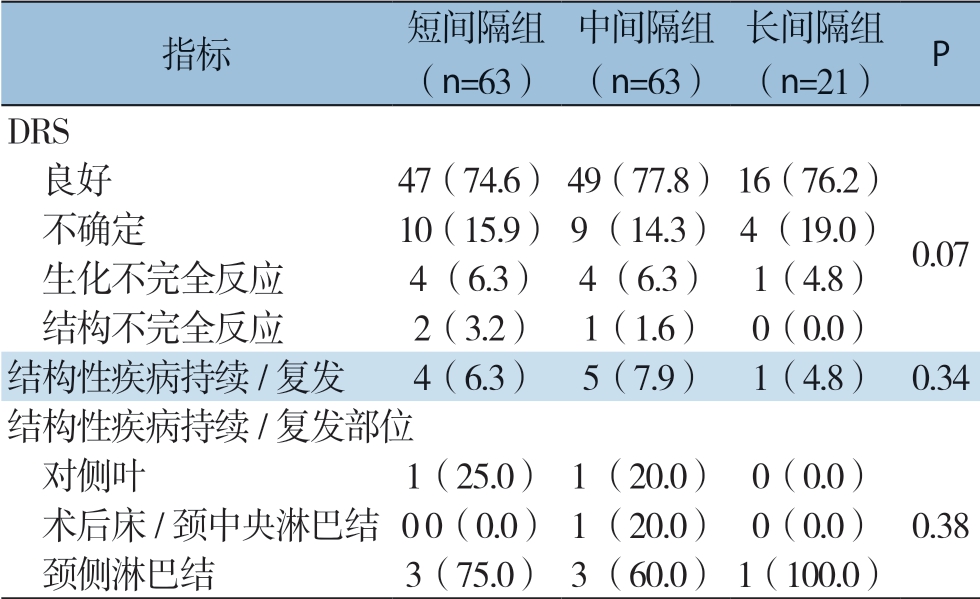

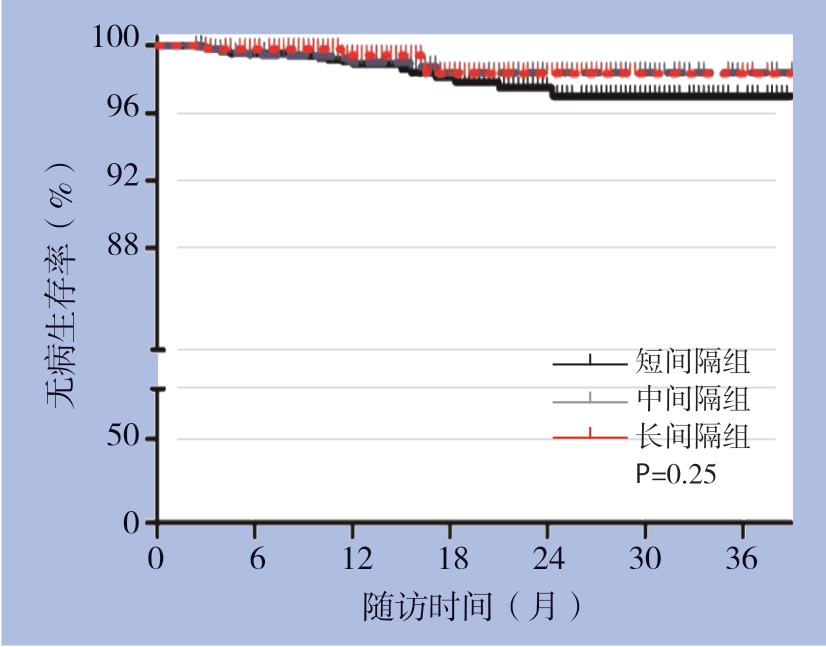

本研究对PTMC患者初始治疗后的DRS进行比较,结果显示,3组患者间DRS分类无统计学差异(P=0.07)。短间隔组47例(74.6%),中间隔组49例(77.8%)、长间隔组16例(76.2%)患者反应良好。短间隔组2例(3.2%)、中间隔组1例(1.6%)患者表现为结构不完全反应。随访期间,短间隔组4例(6.3%)、中间隔组5例(7.9%)、长间隔组1例(4.8%)表现为结构性复发/疾病持续。从初始手术到结构性复发/疾病持续发生的平均时间为(3.3±1.1)年,3组患者间结构性复发/疾病持续发生率(P=0.34)、结构性复发/疾病持续的部位(P=0.38)及DFS(P=0.25)均无统计学差异(表2)(图1)。

表2 个体危险因素匹配后的PTMC患者的临床结局[n(%)]

Table2 Clinical outcomes of PTMC patients after individual risk factor matching [n (%)]

指标 短间隔组(n=63)中间隔组(n=63)长间隔组(n=21) P DRS 良好 47(74.6)49(77.8)16(76.2) 不确定 10 (15.9)9 (14.3)4 (19.0) 生化不完全反应 4 (6.3) 4 (6.3) 1(4.8) 结构不完全反应 2(3.2) 1(1.6) 0(0.0)结构性疾病持续/复发 4(6.3) 5(7.9) 1(4.8) 0.34结构性疾病持续/复发部位 对侧叶 1(25.0)1 (20.0) 0(0.0) 术后床/颈中央淋巴结0 0(0.0)1 (20.0) 0(0.0) 0.38 颈侧淋巴结 3(75.0)3 (60.0)1(100.0)0.07

图1 个体危险因素匹配后3组患者DFS曲线

Figure1 DFS curves of the three groups of patients after individual risk factor matching

2.3 PTMC患者结构性复发/疾病持续的危险因素分析

对个体危险因素匹配后的PTMC患者结构性复发/疾病持续的危险因素分析后发现,男性(HR=2.43,95% CI=1.21~4.91,P=0.013)和多灶性肿瘤(HR=2.45,95% CI=1.24~4.83,P=0.010)是独立的危险因素。甲状腺手术延迟期与PTMC患者结构性复发/疾病持续发生风险无关(表3)。

表3 PTMC结构性复发/疾病持续危险因素的单因素和多因素分析

Table3 Univariate and multivariate analyses of risk factors for structural recurrent/persistent disease of PTMC

因素 单因素 多因素HR(95% CI) P HR(95% CI) P年龄(≥45岁) 0.84(0.42~1.70) 0.63 — —性别(男性) 2.54(1.26~5.11) <0.001 2.43(1.21~4.91) 0.013手术范围(甲状腺全切除术) 1.12(0.57~2.22) 0.74 — —原发肿瘤直径(>0.5 cm) 2.24(1.08~4.67) 0.031 1.76(0.83~3.75) 0.14微小甲状腺外侵袭 1.59(0.82~3.09) 0.17 — —多灶性 3.01(1.55~5.85) 0.001 2.45(1.24~4.83) 0.010颈部中央淋巴结转移 2.18(1.12~4.23) 0.022 1.77(0.90~3.49) 0.10手术延迟期 — — — — 短间隔组 参考值 — — — 中间隔组 0.76(0.37~1.54) 0.44 — — 长间隔组 0.59(0.17~2.00) 0.40 — —

3 讨 论

本研究评估了延期甲状腺手术对PTMC患者长期临床结果的影响。经患者年龄、性别、手术范围、超声测量的初始PTMC直径、甲状腺外侵袭、多灶性肿瘤和最终病理显示的颈部中央淋巴结转移等临床参数匹配后,根据甲状腺手术延迟期时间,将患者分为3组:6个月内、6~12个月和12个月以上。结果发现3组间DRS分类和PTMC患者结构性复发/疾病持续的发展无统计学差异。研究结果表明,延期手术不影响PTMC低风险患者的长期临床结局。

近年来,我国甲状腺癌的发病率呈不断上升趋势,其中新增病例中PTMC的占比非常高,目前甲状腺癌的治疗仍以外科切除为主[9-10]。由于治疗效果好,患者预后佳,PTMC被称为“良癌”或者“惰性癌”[11]。绝大多数PTMC患者并没有生命危险。因此,近年来,学者们试图采用主动监测的方法对PTMC患者进行保守治疗,这一方法又被称为“延迟手术”,在监测过程中一旦肿瘤发生进展,就立即转为手术治疗[4,12]。主动监测是一种保守的观察方法,并且在首次报道时就获得了广泛关注[13]。一项日本学者进行的的回顾性观察研究验证了主动监测的有效性[5],但主动监测期间,PTMC患者存在疾病进展的风险,尤其是年轻患者[14]。有研究报道,主动监测期间疾病进展可以通过甲状腺手术成功治疗[15-17],但长期的临床结局尚未明了。以往多项研究证实主动监测并未增加PTMC患者复发、转移及死亡风险[18-20]。主动监测过程中,一旦患者发生不良症状或出现符合手术的影像学指征,患者立刻转为手术治疗。Ito等[21]对1 465例接受主动监测的PTMC患者进行前瞻性随访,结果显示主动监测5年后,肿瘤增大率仅为5%。目前,在PTMC患者中日本大力推广主动监测,超过50%的低风险PTMC使用主动监测[19]。Sakai等[22]对360例PTMC患者进行前瞻性主动监测,主动监测时间长达9年,监测过程中,32例患者肿瘤直径增加,5例患者发生淋巴结转移,弱钙化和富血管是肿瘤增大的危险因素,年龄较小是淋巴结转移发展的预测因子。Miyauchi等[23]从1993年开始对2 000多例低风险PTMC患者进行主动监测,并将立即手术与主动监测的结果进行了比较,结果显示8%的患者在主动监测10年后肿瘤直径增大3 mm或更多,而有3.8%的患者主动监测10年发生淋巴结转移。即刻手术组的不良事件如暂时性声带麻痹以及暂时性和永久性甲状旁腺功能减退的发生率明显高于主动监测组。因此,该文作者强烈建议将主动监测作为低危PTMC治疗的最佳选择。2015年美国甲状腺协会也将主动监测作为极低风险甲状腺癌患者即时手术的一种替代方法[24-25]。本组患者中,与 6个月内手术相比,延期手术(平均在初始诊断后17个月)与结构性复发/疾病持续风险增加无关。对于诊断到甲状腺手术的不同延迟时间的患者,初始治疗后DRS分类也无统计学差异。尽管本研究中延期手术患者并未在主动监测期间疾病进展,但本研究结果也表明,在初始诊断后延期1~2年手术并未产生不良影响,并间接表明对低风险PTMC患者可采取主动监测。

个体风险因素匹配前,长间隔组患者初始诊断后12个月接受手术,与短间隔组和中间隔组相比,年龄较大、男性更多和肿瘤较小。这些因素也是已知的PTMC复发相关因素[26-30],可能影响外科医生的手术决策。因此,本研究进一步评估了延期手术对经过患者年龄、性别、原发肿瘤直径以及手术范围的个体匹配后PTMC患者临床结局的影响。此外,超声发现的可疑结节的数量或位置也影响手术决策[12];因此,本研究也对其他病理学变量进行了匹配,例如甲状腺外侵袭、多灶性肿瘤和颈部中央淋巴结转移。这些匹配的参数中,只有男性和多灶性肿瘤是PTMC患者结构性复发/疾病持续的独立危险因素,手术延迟时间与PTMC患者结构性复发/疾病持续的风险无关。

总之,本研究结果表明,经过个体风险因素匹配后,PTMC患者延期手术与结构性复发/疾病持续发生风险增加无关,该研究表明,对于PTMC患者可在主动监测情况下,进行延期手术治疗。

[1] Liu Z,Huang T.Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma and active surveillance[J].Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol,2016,4(12):974-975.doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30269-8.

[2] 郭真,卢崇亮.甲状腺微小乳头状癌的研究进展[J].中国普通外科杂志,2012,21(5):597-601.

Guo Z,Lu CL.Research advances in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma[J].Chinese Journal of General Surgery,2012,21(5):597-601.

[3] Nickel B,Brito JP,Moynihan R,et al.Patients' experiences of diagnosis and management of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma:a qualitative study[J].BMC Cancer,2018,18(1):242.doi:10.1186/s12885-018-4152-9.

[4] 李超,蔡永聪,孙荣昊.甲状腺微小乳头状癌:选择手术还是非手术主动监测?[J].肿瘤预防与治疗,2019,32(12):1045-1050.doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-0904.2019.12.002.

Li C,Cai YC,Sun RH.Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma:Surgery or Active Surveillance?[J].Journal of Cancer Control and Treatment,2019,32(12):1045-1050.doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-0904.2019.12.002.

[5] Oda H,Miyauchi A,Ito Y,et al.Incidences of Unfavorable Events in the Management of Low-Risk Papillary Microcarcinoma of the Thyroid by Active Surveillance Versus Immediate Surgery[J].Thyroid,2016,26(1):150-155.doi:10.1089/thy.2015.0313.

[6] Cheng F,Chen Y,Zhu L,et al.Risk Factors for Cervical Lymph Node Metastasis of Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma:A Single-Center Retrospective Study[J].Int J Endocrinol,2019,2019:8579828.doi:10.1155/2019/8579828.

[7] 中国抗癌协会甲状腺癌专业委员会(CATO).甲状腺癌血清标志物临床应用专家共识(2017版)[J].中国肿瘤临床,2018,45(1):7-13.http://dx.doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-8179.2018.01.265.

Chinese Association of Thyroid Oncology (CATO).Expert consensus on clinical application of serum markers for thyroid cancer (2017 edition)[J].Chinese Journal of Clinical Oncology,2018,45(1):7-13.http://dx.doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-8179.2018.01.265.

[8] 中国临床肿瘤学会指南工作委员会甲状腺癌专家委员会.中国临床肿瘤学会(CSCO)持续/复发及转移性分化型甲状腺癌诊疗指南-2019[J].肿瘤预防与治疗,2019,12(32):1051-1080.doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-0904.2019.12.003.

Expert Panel on Thyroid Cancer,Guidelines Working Committee of Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology,Guidelines of Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO):Persistent/Recurrent and Metastatic Differentiated Thyroid Cancer-2019[J].J Cancer Control Treat,2019,12(32):1051-1080.doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-0904.2019.12.003.

[9] 于洋,关海霞.肥胖与甲状腺癌:已知证据的思考和未来研究的展望[J].中华内科杂志,2019,58(1):5-9.doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2019.01.002.

Yu Y,Guan HX.Obesity and thyroid cancer:known and unknown[J].Chinese Journal of Internal Medicine,2019,58(1):5-9.doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2019.01.002.

[10] 任艳军,刘庆敏,葛明华,等.2010—2014年浙江省肿瘤登记地区甲状腺癌发病和死亡情况分析[J].中华预防医学杂志,2019,53(10):1062-1065.doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253?9624.2019.10.021.

Ren YJ,Liu QM,Ge MH,et al.Incidence and mortality of thyroid cancer in cancer registries of Zhejiang Province,2010-2014[J].Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine,2019,53(10):1062-1065.doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253?9624.2019.10.021.

[11] Kaliszewski K,Diakowska D,Wojtczak B,et al.The occurrence of and predictive factors for multifocality and bilaterality in patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma[J].Medicine (Baltimore),2019,98(19):e15609.doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000015609.

[12] 卓宪华,万云乐.积极监测:低风险甲状腺微小乳头状癌的一线治疗?[J].岭南现代临床外科,2019,19(5):513-519.doi:10.3969/j.issn.1009-976X.2019.05.001.

Zhuo XH,Wan YL.Active monitoring:first-line treatment of low-risk thyroid micropapillary carcinoma?[J].Lingnan Modern Clinics in Surgery,2019,19(5):513-519.doi:10.3969/j.issn.1009-976X.2019.05.001.

[13] Sugitani I,Toda K,Yamada K,et al.Three distinctly different kinds of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma should be recognized:our treatment strategies and outcomes[J].World J Surg,2010,34(6):1222-1231.doi:10.1007/s00268-009-0359-x.

[14] Kandil E,Noureldine SI,Tufano RP.Thyroidectomy vs Active Surveillance for Subcentimeter Papillary Thyroid Cancers--The Cost Conundrum[J].JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg,2016,142(1):9-10.doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2015.2852.

[15] Miyauchi A,Ito Y,Oda H.Insights into the Management of Papillary Microcarcinoma of the Thyroid[J].Thyroid,2018,28(1):23-31.doi:10.1089/thy.2017.0227.

[16] Jeon MJ,Lee YM,Sung TY,et al.Quality of Life in Patients with Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma Managed by Active Surveillance or Lobectomy:A Cross-Sectional Study[J].Thyroid,2019,29(7):956-962.doi:10.1089/thy.2018.0711.

[17] Ito Y,Miyauchi A.Active Surveillance as First-Line Management of Papillary Microcarcinoma[J].Annu Rev Med,2019,70:369-379.doi:10.1146/annurev-med-051517-125510.

[18] Ito Y,Miyauchi A,Oda H.Low-risk papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid:A review of active surveillance trials[J].Eur J Surg Oncol,2018,44(3):307-315.doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2017.03.004.

[19] Ito Y,Miyauchi A,Kihara M,et al.Patient age is significantly related to the progression of papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid under observation[J].Thyroid,2014,24(1):27-34.doi:10.1089/thy.2013.0367.

[20] Sugitani I,Ito Y,Miyauchi A,et al.Active Surveillance Versus Immediate Surgery:Questionnaire Survey on the Current Treatment Strategy for Adult Patients with Low-Risk Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma in Japan[J].Thyroid,2019,29(11):1563-1571.doi:10.1089/thy.2019.0211.

[21] Ito Y,Miyauchi A,Inoue H,et al.An observational trial for papillary thyroid microcarcinoma in Japanese patients[J].World J Surg,2010,34(1):28-35.doi:10.1007/s00268-009-0303-0.

[22] Sakai T,Sugitani I,Ebina A,et al.Active Surveillance for T1bN0M0 Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma[J].Thyroid,2019,29(1):59-63.doi:10.1089/thy.2018.0462.

[23] Miyauchi A.Clinical Trials of Active Surveillance of Papillary Microcarcinoma of the Thyroid[J].World J Surg,2016,40(3):516-522.doi:10.1007/s00268-015-3392-y.

[24] Haugen BR.2015 American thyroid association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer:What is new and what has changed?[J].Cancer,2017,123(3):372-381.doi:10.1002/cncr.30360.

[25] Haugen BR,Alexander EK,Bible KC,et al.2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer:The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer[J].Thyroid,2016,26(1):1-133.doi:10.1089/thy.2015.0020.

[26] Tuttle RM,Fagin JA,Minkowitz G,et al.Natural History and Tumor Volume Kinetics of Papillary Thyroid Cancers During Active Surveillance[J].JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg,2017,143(10):1015-1020.doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2017.1442.

[27] Pisanu A,Saba A,Podda M,et al.Nodal metastasis and recurrence in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma[J].Endocrine,2015,48(2):575-581.doi:10.1007/s12020-014-0350-7.

[28] Jeon MJ,Kim WG,Choi YM,et al.Features Predictive of Distant Metastasis in Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinomas[J].Thyroid,2016,26(1):161-168.doi:10.1089/thy.2015.0375.

[29] Siddiqui S,White MG,Antic T,et al.Clinical and Pathologic Predictors of Lymph Node Metastasis and Recurrence in Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma[J].Thyroid,2016,26(6):807-815.doi:10.1089/thy.2015.0429.

[30] Mercante G,Frasoldati A,Pedroni C,et al.Prognostic factors affecting neck lymph node recurrence and distant metastasis in papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid:results of a study in 445 patients[J].Thyroid,2009,19(7):707-716.doi:10.1089/thy.2008.0270.